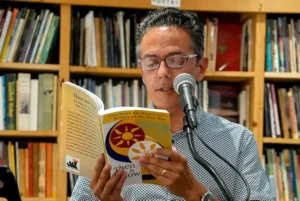

How Dilshod Rizam Turned an Online Art Course into a Digital Studio. A Conversation with Professor Dilshod Rizam, Art Instructor at Cosumnes River College.

At first, it looks nothing like an art class.

No smell of paint. No easels leaning against the wall. No charcoal dust on hands or sleeves. Just a Canvas page loading on a laptop somewhere in California. A student uploads an image hesitant lines, careful shading, a composition that quietly apologizes for itself.

A few hours later, feedback appears.

Not a blunt grade. Not a checklist. A paragraph. Calm. Specific. What works. What doesn’t. What to try next. And one sentence students tend to remember long after the semester ends: “Keep going. You’re closer than you think.”

This is how Professor Dilshod Rizam teaches art today through screens, files, and sustained attention. From his online courses at Cosumnes River College, he has built something that feels increasingly rare: a digital studio where students who arrive convinced they “can’t draw” slowly begin to trust their eyes and hands.

One former student later wrote in an anonymous course evaluation:

“I never thought I could draw until this class.”

Rizam doesn’t perform enthusiasm. He doesn’t romanticize talent. He doesn’t sell inspiration. Instead, he teaches patience how to look longer than feels comfortable, how not to panic when a drawing fails, how to return to the work. In an era when online education often feels automated and rushed, his classes move deliberately, almost quietly.

To understand how he arrived here, you have to look beyond the screen. Back to Tashkent. Back to theater. Back to a moment when art nearly slipped out of his life altogether.

Before California, There Was Tashkent

Dilshod Rizam was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, a city where art education followed strict traditions. As a child, he drew constantly animals, animated characters, anything with movement. But drawing stopped being a pastime in 1986, when he entered the State Art College named after Benkov.

The training was demanding. Academic drawing. Painting. Long studio hours. Critiques that focused on precision rather than praise. Alongside fine art, Rizam specialized in theater set design a discipline that required more than visual skill.

“You couldn’t design a stage without understanding the story,” he recalls. “We had to read every play completely. Research the period. Architecture. Costumes. How people lived.”

Each sketch served a narrative purpose. Backgrounds were not decorative; they were structural. Theater taught him something that would later shape his teaching: art is not just expression, it is responsibility to context.

For a time, this felt like his future.

When the Plan Didn’t Work

After completing his Associate of Arts degree in 1990, Rizam applied for set designer positions in theaters. None of them worked out.

“A year passed,” he says simply. “I couldn’t find work in my field.”

There was no dramatic collapse just rejection, uncertainty, and the slow realization that the path he had prepared for might not exist. For many artists, this is where art becomes peripheral.

Rizam chose instead to stay close to it.

In 1991, he entered the National Institute of Art named after Kamoliddin Bekzod, earning his Bachelor of Arts in 1995 and a Master of Fine Arts in 1997. Teaching entered his life not as a compromise, but as a way forward.

“I had strong teachers,” he says. “They mattered more than talent.”

Finding a Place in America

Rizam later relocated to California, where his professional life developed gradually. He continued working as an artist, taking commissioned projects: portraits, landscapes, murals mostly for private clients in the greater Sacramento area.

His work moved into homes, churches, restaurants. Art became part of daily spaces rather than institutions. One project, in particular, brought his past and present together.

A Wall That Carries a Homeland

At Caravan Uzbek Cuisine in Citrus Heights, a panoramic mural stretches across the interior. Uzbek architecture. Desert landscapes. Caravan riders moving slowly across history.

“I wanted people to feel where they were,” Rizam says. “Not just eat food, but enter a place.”

The project demanded the same habits he learned decades earlier in theater: research, accuracy, patience. He studied traditional clothing, architectural details, Central Asian geography. Uzbekistan’s role in the Silk Road the connection between East and West became a quiet narrative running through the mural.

For visitors unfamiliar with the region, the painting offers atmosphere. For Rizam, it holds memory.

Teaching Students Who Don’t Believe in Themselves

Back in his online classroom, Rizam encounters a different challenge.

“Most students arrive already convinced they’re not artists,” he says.

One student submitted unfinished work, repeatedly apologizing in the comments. Rizam ignored the apology and focused on the process.

“I told them: stop trying to be good. Try to be honest.”

The progress was gradual. No sudden transformation. But by the end of the course, the student’s work carried confidence rather than fear.

“That’s what changes,” Rizam says. “Not perfection. Trust.”

What Online Teaching Taught Him

Teaching online forced Rizam to rethink everything. Without the ability to physically intervene, instructions had to be precise. Feedback had to be clear. Students had to learn to observe their own process.

“They document everything,” he explains. “They see their mistakes and their progress.”

Paradoxically, distance created attention. Slowing down became part of the method.

“It made me a better teacher,” he says. “And a better artist.”

What Remains

Rizam doesn’t talk about legacy in grand terms. He talks about habits.

Learning to look longer.

Not quitting when something fails.

Understanding that art isn’t talent, it’s attention.

In a digital world built for speed, his classes insist on slowness. On staying with the work.

In his digital studio, he continues doing what he has always done: teaching people to see.