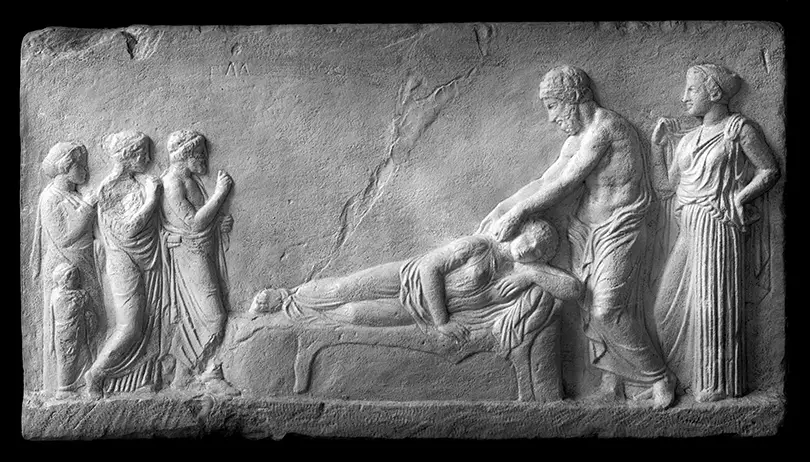

In ancient Greece, if an Athenian statesman fell ill, he might enter an Asclepieia sanctuary where patients were treated with art, music, poetry and prayer on top of clinical therapies. A typical patient would have been a soldier, perhaps with a broken leg from the Greco-Persian Wars. Upon entering the sanctuary, patients called “petitioners” or pilgrims would receive a purification rite of bathing, rest and sometimes take part in sacrificial ceremonies before seeing priest-doctors.

Physical treatment would entail resetting broken bones by hand, followed by dousing the wound with an antiseptic concoction of wine and vinegar. For pain, they’d ingest willow bark tea or apply opium paste to the wound. The soldier’s leg would be stitched up with dried ox tendons, then wrapped with a protective dressing of linon, an airy material of woven dried fibrous flax threads, a textile still seen draped over Santorini beachcombers today.

The injured weren’t sent hobbling home immediately, as is often done in a modern Western hospital. The Asclepieia healing regime consisted of enkoimesis (a deep sleep in a sacred space) and epiphany (when gods appeared in dreams). This healing sanctuary also provided therapeutic arts such as music, theater, poetry, prayer, massage, herbal treatments, hot spring soaks, walking meditation and symbolic offerings. Think: hospital, spa and meditation center, merged with an art retreat.

The Hellenic Asclepiad priest-doctors were holistic experts in physical disease as well as illnesses of the mind and spirit. After providing musculoskeletal care, they would assess the appropriate follow-up treatment that included spiritual, psychological and physiological protocol for the patient.

To avoid misuse of medicinal and spiritual applications, such as using phytotherapy to create poisonous cocktails or conducting spiritual rituals with power and domination over the weak, the priest-doctors joined a brotherhood pact to guard their healing wisdom. Sworn to secrecy, the Asclepiad structure prevented medical quacks from running amok and ensured their methodologies were implemented for the common good.

Convalescence and rehabilitation can get quite boring and isolating, but not in the Asclepieia routine. There was much more activity than lying alone patiently in a cold, austere room. The priest-doctors customized a regimen according to the needs of the petitioners. Temple workers chanted at bedsides and encouraged them to take contemplative walks through labyrinths located on the complex grounds. Some housed amphitheaters on the premises or at least within walking distance. Petitioners could shuffle across the grounds peppered with sculpture and watch “Prometheus Bound” by Aeschylus.

Common themes of divine justice, human suffering and transformation uplifted the spirits of the disheartened and ill, discouraged by their misfortune. The Hellenes believed that theater served as an emotional release and, therefore, was therapeutic to the soul and mind. If the patient needed a lighter fare, slapstick comedies, lewd jokes and jokers in masks served as a form of laughter therapy. Today, we call these masked comedians who uplift patients’ spirits “medical clowns.”

While the Asclepieia seems like a relic of the past, today we see similar holistic programs in local Sacramento institutions that have been integrating the arts in healing.

How art programs help with healing

Fast forward to 2025, Sacramento hospitals, correctional facilities, senior and youth centers have adopted their version of a holistic Asclepiean approach. More and more public institutions and community service organizations design and implement programming to include cultural and contemplative arts healing.

For instance, Kaiser Permanente’s Sacramento Medical Center has a meditation room where patients may pray and meditate. The UC Davis Medical Center CARE Project also provides art therapy and the Japanese energy healing technique, Reiki. The Sutter Center for Psychiatry in Davis provides music and dance therapy for patient rehabilitation. On a given day at the Pathways Recovery Addiction Treatment Center in Sacramento, for example, members participate in photo-collaging, ceramics and watercolor painting.

The “arts as medicine” philosophy isn’t confined to hospitals or treatment centers; it occurs in unlikely places like prisons, where creative workshops have become effective in addressing mental and emotional challenges such as anger management, depression, anxiety and stress.

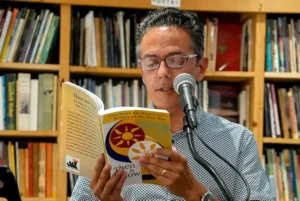

In 2024, Sacramento State’s School of Music and the Department of Art mentored incarcerated individuals of Folsom State Prison who had been learning how to implement art workshops with fellow inmates. Erin Kaplan, who runs the program, remarks, “In institutions of incarceration, vulnerability can be incredibly dangerous, yet it is essential to theater that all participants are willing to be open and honest. By creating this kind of space for individuals, we create an ensemble in which everyone holds one another up, supports one another, and cares for one another, and in doing that, we heal each other.”

Similar types of arts rehabilitation programs have been researched by major universities, where scientists document and gather evidence of how cultural participation affects the brain, body and emotional well-being.

Since the 1990s, university research labs such as Johns Hopkins University International Arts and Mind Lab, New York University Jameel Arts & Health Lab, and the University of Florida Health, Shands Arts in Medicine program have focused on empirical evidence to demonstrate the restorative benefits of cultural experiences like theater, poetry, visual arts, meditation and comedy. The University of Florida Center for Arts in Medicine program emphasizes “social or arts prescribing” whereby health professionals recommend non-clinical experiences like music, dance or painting to accelerate emotional, psychological and physical healing. Instead of prescribing pharmaceuticals, doctors might instruct patients to engage in social activities like painting or dance class, or attend a concert or theatrical play or adopt a meditation regimen.

At Johns Hopkins, their International Arts + Mind Lab explores neuroaesthetics or how the brain and body respond to the arts. The IAM Lab bridges art, architecture, music and brain science to inform healing design and therapeutic environments. Since 1996, the University of Florida has offered degrees to both undergraduate and graduate students in Arts in Medicine.

With scientific evidence demonstrating that art heals, it’s not a stretch to see how investing in arts education, like California’s Proposition 28, could shape resilient communities.

Art belongs in the classroom

Research shows that the arts as medicine can serve as powerful preventive care and rehabilitation for depression, anxiety, loneliness, low self-esteem, PTSD and addiction. At a time when suicide rates and cyberbullying among American youth are at critical levels and California schools finally have a significant arts budget, we have an opportunity to address these crises with an art curriculum designed for social impact.

This means moving beyond seeing art as mere entertainment and beauty, and recognizing it as a form of cultural prescription that belongs in our classrooms.

Thanks to Proposition 28 Arts and Music in Schools Funding Guarantee and Accountability Act, which went into effect in the 2023-24 school year, more California school children are accessing robust arts programming. This school year, students will be picking up paint brushes, guitars, clay, masks and dance shoes alongside math and history books. School administrators and curriculum designers across the state have been convening to hire hundreds of teaching artists and art teachers to expand their arts programming.

To clarify, art hasn’t been totally absent from California schools; it just hasn’t been a priority since educational budget cuts of the 1970s, when art teachers slowly disappeared in most secondary schools. Due to the slashing of arts education spending over five decades, California became one of the lowest spenders on providing art enrichment to our kids, ranking the richest state in the United States a dismal 37th place nationally in arts funding. Given California’s struggle in the past to prioritize the arts in schools, reframing arts education as an investment in public well-being could help sustain funding long term.

Many school art classes center on individual expression, cultural appreciation and art for art’s sake. In a utilitarian society with a philosophy favoring a vocational education over an intellectual liberal arts one, funding arts education for those aforementioned reasons can be difficult to justify. However, what if, like the University of Florida or Johns Hopkins, we demonstrate how art education can be implemented in the health care sector, one of the largest sectors of expenditure in the United States?

When we teach music, theater, poetry, dance, visual art, creative tech and film as tools for healing, we catalyze collaboration and empathy, laying the foundation for stronger, healthier communities. Following the wisdom of the ancient Greek healing sanctuaries, California schools may now stand at the forefront of demonstrating that the progress of a nation is inseparable from the health of our creativity.

Sacramento native Angie Eng is a conceptual artist and educator who has lived in New York City, Paris, Mexico, and Ethiopia. She holds a Ph.D. in intermedia arts, writing and performance, and has received over 50 grants, commissions and residencies for her creative work. She teaches at New York University and is an independent writer for Solving Sacramento and Artist Organized Art.

This story was funded by the City of Sacramento’s Arts and Creative Economy Journalism Grant to Solving Sacramento. Following our journalism code of ethics and protocols, the city had no editorial influence over this story and no city official reviewed this story before it was published. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Hmong Daily News, Outword, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review and Sacramento Observer. Sign up for our “Sac Art Pulse” newsletter here.

By Angie Eng