Inside the decade-long struggle to make Joshua’s House a reality in Sacramento

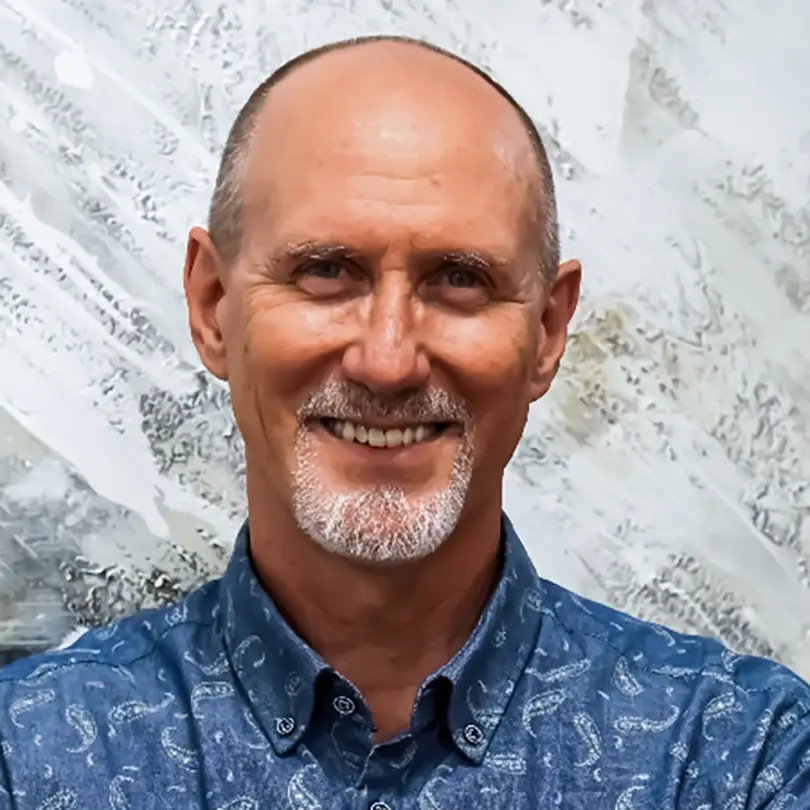

Craig Dresang has lived in the shadow of death since he was 8 years old.

Dresang was in third grade when his mother, Joyce, was diagnosed with stage 3 cancer. At almost the same moment, his mom’s best friend was also given a devastating cancer diagnosis. She was gone six months later — an outcome that kept flashing in Dresang’s young mind. His own mother fought and held on for years, which meant Dresang’s entire childhood was spent wondering when he’d lose her.

“I was always expecting,” Dresang recalls, “always anticipating.”

In the end, it was his parents’ inability to afford the out-of-pocket expenses of an anti-cancer maintenance drug that probably cost Joyce her life. That was an early lesson for Dresang about the American health care system’s realities. He’d have many more in the coming years.

Dresang went on to work for Alexian Brothers Bonaventure House in Chicago, which is a homeless shelter for people who had an HIV/AIDS diagnosis and were simultaneously struggling with severe addiction issues. This was during the 1980s when the AIDS virus was bringing a wave of death to the U.S. People were terrified of it. Elected officials wanted to ignore it. Not only was Dresang deep in the trenches, his aunt, a Franciscan nun, launched a campaign to build the first supportive housing facility in Illinois for families coping with an HIV diagnosis. Dresang ultimately spent much of his career developing hospice centers in the Midwest and converting old buildings into serene spots for people to live out their final days.

The child who could never run from death became the professional willing to confront it.

Dresang later moved to Davis and took a job with YoloCares, the oldest, best-established hospice provider in the Sacramento region. That led him to meet Marlene von Friedrichs-Fitzwater, a woman on a mission to create the first hospice shelter for unhoused people on the West Coast. She couldn’t have known that this arduous task would be completed right as a U.S. president cut Medicaid and food assistance programs for the poorest Americans most at-risk of becoming homeless, then defunded Housing First grants that have traditionally helped get people off the streets.

The war on final rest

Von Friedrichs-Fitzwater’s relentlessness was driven by loss: Her grandson, Joshua, met a tragic end while living on the streets of Omaha, Nebraska. Von Friedrichs-Fitzwater wanted to forge an unconditional apparatus of comfort and dignity in her hometown of Sacramento, one that would also serve as a remembrance of her grandson’s life. Given his background, Dresang didn’t hesitate to join the board of Joshua’s House in 2016.

For nearly a decade, Dresang had a front seat to the byzantine journey the project was on, being met with logistical problems and entrenched resistance at each property it was proposed for. But the real wake-up call came in the summer of 2023. At that point, through the efforts of former Sacramento city councilman Jeff Harris, the board at Joshua’s House had finally located a workable property in the city’s Northgate neighborhood. But now Harris was out of office — and residents in Northgate were being told they should have serious concerns about Joshua’s House.

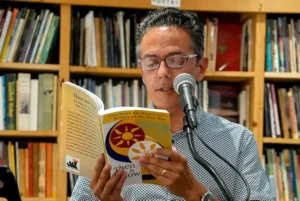

The 1.2-acre site that was finally settled upon is next to Garden Valley Elementary School. It wasn’t long before leaflets were circulating through the neighborhood that warned of a problematic future for the campus if Joshua’s House broke ground. In-coming city councilwoman Karina Talamantes and some trustees for the Twin River Unified School District responded by hosting a city council meeting. Dresang was frustrated that this critical gathering was scheduled for a night when von Friedrichs-Fitzwater was out of town. He asked Chris Erdman, a coworker at YoloCares, if they should sit in the audience just to hear what was being said.

Prior to this, Erdman had spent 35 years supporting unhoused individuals as a parish minister in cities like Fresno and Davis. His motivation to be part of Joshua’s House came from an insight that a struggling parishioner once shared with him.

“He said, ‘Chris, dying is hard,’” Erdman reflects, “‘but dying alone and on the streets is hell.’”

Erdman, Dresang and a YoloCares grief specialist named Elisa Stone decided to attend the town hall.

They were soon listening to speaker after speaker predict all the ways that Joshua’s House would trash the neighborhood and traumatize young school children. Opponents claimed the hospice shelter would lead to naked people lounging around across from the classrooms. They also worried that school buses would be rolling by distracting lines of transient people who were desperate for food and medications. They asserted that hand-to-hand drug deals, including ones involving deadly fentanyl, would be taking place around the edges of Garden Valley’s campus. They even wondered aloud if kids on the playground would be watching draped corpses getting carted out of the hospice on gurneys. And these opponents emphasized, in a broader sense, that having any proximity to death would be ultimately harmful to the children.

That last idea made Dresang sigh. YoloCares is one of the only nonprofits in the area with a children’s bereavement program. When it comes to local mental health services, YoloCares is the go-to organization for everything from when kids lose someone to childhood cancer and car accidents, to gun violence, drug overdoses and suicide. And Dresang knows from his own upbringing that some children will never escape these questions.

“We have the science to support this: Our best bet with kids is to try to normalize death,” Dresang observes. “And I can identify with that. It sure would have been helpful if the schools I was in, or the community, could have talked to me about that when my mom was sick.”

Dresang didn’t press this point at the confrontational meeting, though Stone did respectfully tell the opponents that she was a death counselor for children and suggested this could be a teaching opportunity if approached the right way. Erdman remembers that offer from Stone being met with so much hostility that Sacramento police officers escorted all three members of YoloCares to their cars.

“That’s when I realized what Marlene was really up against,” Dresang says.

Erdman agrees, adding that, “In the fog of war, a narrative was created that’s been hard to outlive.”

But now that narrative is being crushed in real time, ironically, in the saddest way possible — by someone who is dying.

Voices from the shadows

Scott Kirchner still remembers the trepidation that came with sleeping alone in camps and alleys.

In the early 1980s, Kirchner was recently out of the U.S. Air Force and deep in the throes of addiction. He found himself living outside in Yuba City. There was part of his mind that knew he was vulnerable to predation without walls to protect him at night. He slept with a gun, though what he would have actually done with it, he has no idea. But another part of Kirchner’s mind had decided that the fear had its limits.

“I didn’t really care about my health,” he admits. “If you’re familiar with Maslowian psychology, it’s about the hierarchy of needs. You just take care of your basic needs first. So, I wasn’t worried so much about tomorrow.”

Yuba City was a smaller community back then, and one that wasn’t flooded with cheap drugs laced with fentanyl. Kirchner remembers the presence of death in its homeless camps as more of a slow-motion phenomenon. People living with addiction or mental health problems would linger on for years, he says, though he’s also quick to admit that if anyone did die on the streets around him, he probably wouldn’t have known right away.

“When I was out there, I was pretty self-centered,” he explains. “I was just looking at my own feet, feeling like shit about myself.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs eventually connected Kirchner with in-patient treatment. That, in turn, introduced him to the 12-step program. Kirchner has been an active member of the 12-step community ever since. He got housed, hit new education goals and eventually became a professor of human communications at Sacramento State. It was while teaching college students that he first heard about von Friedrichs-Fitzwater’s quest to build Joshua’s House.

“I’ve maintained my clean date; but along with that, I found another way to live,” Kirchner notes of his mindset at the time. “I was looking for a way to give back. Getting involved in Joshua’s House just made sense. Having been without a home for three years, and knowing what that’s like, it is personal to me.”

And von Friedrichs-Fitzwater was finding ways to use other personal stories to rally others. After her grandson’s death, von Friedrichs-Fitzwater and a volunteer named Jose Martinez started conducting interviews with people living on Sacramento’s avenues and riverbanks. They would eventually speak with more than 200 individuals, some of whom were seriously ill. Von Friedrichs-Fitzwater asked them about their access to health care, whether they were diabetic or not, and how they dealt with issues like medication that needed to be refrigerated.

“I became aware that there were people living on the streets who had cancer,” von Friedrichs-Fitzwater shared in a 2016 speech. “As a cancer survivor myself, I could not even imagine what that would be like. … Hospitals are typically discharging them out onto the streets because there isn’t any place for them to go.”

During that same address, von Friedrichs-Fitzwater showed a photo of a woman named Ana.

“Ana was a homeless woman who had advanced lung cancer,” von Friedrichs-Fitzwater continued. “And her biggest fear was dying alone on the streets and being forgotten — that no one would remember that she had ever lived or existed. And, sadly, that’s what happened.”

Before her talk was over, von Friedrichs-Fitzwater showed a picture of another face.

“Dan is a homeless man in our community who has heart failure, Type 2 diabetes and COPD,” she details. “He ended up homeless about four years ago when he lost his business, his house, and his wife to cancer. And his greatest fear was that he would get sicker and sicker and die alone in his camp.”

Such first-hand accounts, along with von Friedrichs-Fitzwater’s personal tenacity, are what drew former councilmember Harris into becoming a politician who’d fight tooth-and-nail for Joshua’s House.

“When it came to my first impressions of Marlene, she’s small in stature, but you could tell by the light in her eyes that she had a lot going on — I liked her immediately,” Harris muses, thinking back a decade. “As we talked, we realized we had a lot in common. For instance, I was the hospice worker for my own mom when she died. For six weeks, I took care of her 24/7. So, I know what dying from cancer looks like.”

Harris started holding community meetings to bring people together around the project. Meanwhile, as Kirchner settled in at the Joshua’s House board, he took on the role of acting as a sounding board for von Friedrichs-Fitzwater’s various strategies. Sometimes he was there to be a helpful contrarian, though he says even those instances made him admire von Friedrichs-Fitzwater even more.

“I love her,” Kirchner admits. “Marlene is such a warrior.”

And Joshua’s grandmother had to be tough. Even with Harris in her corner — and the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors later giving unanimous support — Joshua’s House was constantly met with counter offensives. The initial push-back came when von Friedrichs-Fitzwater purchased a building on C Street in the River District (converting that historic structure was ultimately untenable). Then the real dog-pile started once a parcel of city-owned property was essentially donated across from Garden Valley Elementary School.

At that point, Kirchner took on another unofficial duty, examining the opposition’s talking points and identifying the logical fallacies he saw in them. He was surprised he even had to.

“It seems like any social issue can be politicized and create division, and even the notion of homelessness can be divisive, but Marlene’s mission was pretty focused, and I think most people can agree that individuals have the right to die with dignity,” Kirchner notes. “This idea of dying in a bush somewhere, there’s a pathological appeal to that, there’s an emotional appeal to it. I think most people can get that.”

But now Kirchner and other board members like Dresang were finding that people “getting that” was dependent on the care rendered not happening by their homes and schools.

The doors open

On a summer day in mid-August, the staff at Joshua’s House began tending to their first two patients. After setbacks, financial obstacles and stiff political roadblocks, the compassion dream that followed Joshua’s death on the streets some 1,600 miles away is now a reality.

“I appreciate every staff member I encounter,” says Shannon Bustler, who was soon making her eighth visit to see her uncle, Richard Cooper, one of the patients. “Everybody here is just so warm, caring and accommodating.”

She adds, “This seems like home to my uncle, and it’s the first place he’s wanted to stay.”

It took some heavy hitters to make this happen: With leadership from Harris, the Sacramento City Council voted unanimously to support Joshua’s House in May of 2018 and then late offered a 50-year lease on city-owned land for $1; with urging from Sacramento County Board of Supervisors Chair Phil Serna, the county government donated around a $1.5 million from special homeless funds; and recognizing the impact of homelessness on indigenous communities, the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation gave a $1 million grant to get the project across the finish line. Joshua’s House will also serve terminally ill Native Americans who have nowhere to go.

Having surmounted a hill many believed was unconquerable, von Friedrichs-Fitzwater — now struggling with her own health issues — has entrusted the ownership of Joshua’s House to the longtime experts at YoloCares.

“I’m as relieved for Marlene as I am for the community and the folks that we will be serving,” says Kirchner. “It think this shows grassroots organizing is important and powerful, and people should not just give the fuck up. Love, as an action, is not just powerful, but empowering.”

Nick Avdis, a land use attorney who donated eight years of his time to help Joshua’s House deal with legal hurdles, is also resting easier now.

“People had been starting to lose hope, you know, after years of fighting,” Avdis admits. “I would say there were points of despair and disenchantment with the whole situation … I live in the area; and now that it’s open, when I drive to my office, every day, I would look at that. My kids would drive to school, and I would tell them, ‘Forget the other projects I’m working on. This was the passion project.’”

So far, none of the unsettling scenarios that critics forecasted have come to pass. And it’s unlikely that they will. There are no lines of unwell people in various states of undress, partly because Joshua’s House does not provide drop-in programs for the unhoused, nor does it offer any general beds, meals or social programs. Dying people are brought here by referrals, mostly from medical personnel. There’s also no shady volunteers leaking pharmaceuticals into the hands of waiting strangers outside, nor other clandestine activities that would turn the clean collection of tiny homes into an open-air drug market. YoloCares employs professional clinical and medical staff to operate the shelter, and any companionship volunteers present are under their supervision.

According to Erdman, who’s now the onsite manager, when an inevitable death does come to pass at the shelter, it won’t turn into a disruptive spectacle for the school kids. Erdman stresses that those who pass will be taken away with no flashing lights or blaring sirens, but rather they’ll be handled with respect and privacy in mind.

For Emily Halcon, director of Sacramento County’s Department of Homeless Services and Housing, the 15-unit facility is more than an exercise in empathy, it is a chance to learn about handling death in the unhoused population in a different way.

“We are seeing trends of this population aging, as well as the complexity of medical issues that are just natural when you’re living unsheltered,” Halcon points out. “It’s unfortunate to need dedicated hospice beds for those experiencing homelessness, but it’s a reality that if you are living unsheltered, and you have chronic diseases, or are nearing the end of your life, this creates a dignified and safe place to live out the rest of your last days. … I think we can confidently say for those people who travel through Joshua’s House, the end of their life will be less painful.”

While officials agree there is a need for Joshua’s House, determining how many people die on the streets from terminal illness is difficult. A recent Sacramento Bee analysis found that between 2023 and 2024, at least 500 unhoused individuals died in Sacramento County. The year before that, in 2022, the Sacramento Regional Coalition to End Homelessness reported that 203 people died on the streets. Logs from the Sacramento County Coroner’s Office differentiate such deaths along the lines of violence, overdose, suicide, exposure to the elements, pneumonia, blood clots and cardiac arrest, but tracking the unhoused who expire from causes like cancer or chronic heart failure is less precise.

“If someone dies under the care of a physician, their case is not referred to the coroner’s office,” notes Janna Haynes, public information manager for Sacramento County. “So, we are dependent on the hospitals flagging, essentially, that there was a person known to be unhoused that died under their care.”

Regardless of how quickly the beds in Joshua’s House fill up, Erdman believes he has assembled a team that will value their connection to the patients. He’s eager to see how the work they do might lead to broader inspiration.

“This is an experiment, the first of its kind that we know of west of Salt Lake City, and one of the few homeless facilities like this in the country,” Erdman stresses. “We hope that in the next five years, we will inspire five more innovations on this kind of model, so we can begin to make a dent in this huge community problem of homelessness.”

Erdman and his team may be hopeful about getting more suffering people to safety and comfort, but the Trump Administration has been reversing course on some of the most data-driven avenues known to assist the overall unhoused population.

Specifically, Trump’s recent executive order entitled “Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets” directs the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development and Department of Health and Human Services to revise regulations, grant requirements and guidance to cancel support for Housing First policies. Organizations like the Urban Institute argue that “decades of evidence” suggest that the Housing First strategy is one of the best methods for helping those struggling with dire poverty, addiction and mental illness. City and county governments across the Capital Region are still trying to understand how this could affect their overall efforts on homelessness.

As for Dresang, he can’t help but think of Joshua’s House in connection to revelations he had while working in Chicago, back when he’d spend his days speaking with smart, accomplished people who’d become homeless through severe mental illness or unpredictable calamities, and then send his nights fundraising in the mansions of trust fund kids and nepo babies whose wealth was inherited through the luck of a birth lottery.

“Both of these groups of people were the recipients of circumstances beyond their control,” Dresang says. “I realized there should be no judgement because it’s a roll of the dice. And that helped eliminate some of my own bias around the homeless population, and people who were struggling in life. It’s still a reality check for me. You know, don’t be too haughty because if it wasn’t for luck — or grace of God — I could easily be in the shoes of an unhoused person.”

This story is part of the Solving Sacramento journalism collaborative. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Hmong Daily News, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review and Sacramento Observer. Support stories like these here, and sign up for our monthly newsletter.

By Scott Thomas Anderson