One day, there was no tree. The following day, a fully grown strawberry tree sat in the middle of the 1-acre student farm at Food Literacy Center in Sacramento. It took about eight men with a flatbed truck and a Bobcat to get the donated tree on-site and planted.

For the students at the elementary school next door, the seemingly spontaneous sprouting of a large tree overnight was a sight to behold, says the center’s founder and CEO Amber Stott.

“‘Oh my gosh, how’d you get that tree so big?’” Stott recalled students asking with curiosity. The tree is one of the many marvels children find at the farm, a place where they also explore, run around, grow food and search for ladybugs.

“They’re so proud. On Back-to-School Night, we’ll have the doors open and they’ll be like, ‘Mom, I gotta show you this [and] take their parents on tours out here,” Stott said. “They definitely get their wiggles out here. Also a lot of them will tell us they feel very calm. A lot of them will take their little journals and walk around and just sit somewhere.”

Food Literacy Center is celebrating its 15th anniversary, with one of its biggest accomplishments coming in the last few years. In 2021, the nonprofit moved into a new, state-of-the art 4,500-square-foot facility next to Leataata Floyd Elementary School and across the street from the historic Marina Vista public housing in the Upper Land Park neighborhood.

The $4.3 million facility, paid for by Sacramento City Unified School District, includes a cooking classroom, commercial prep kitchen, student farm and offices. FLC teaches children about healthy cooking, nutrition and gardening.

The center is an example of “how to do government right,” Stott said. The facility is the result of a partnership between her nonprofit, SCUSD, which owns the land and facility, and the City of Sacramento.

Nutrition education programs such as FLC may become even more critical as recent cuts by the federal government to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) show the vulnerability of the country’s food safety net. Additionally, inflation has driven up the cost of healthy foods, like fruits and vegetables, and about 20% of U.S. youth between the ages of 2 to 17 are obese.

“We’re trying to get [students] to have access to food, but we want it to be healthy food, and so we have to help change their behaviors so they like healthy food and will eat it,” Stott said. “Our program combines those solutions.”

A dream materializes

Stott has worked in the nonprofit sector her whole career. She started Food Literacy Center as a result of the Great Recession, and the upheaval it caused to everyday people and to nonprofits. She was also reading books on the American “food system,” a concept that had not previously been on her radar.

“There was this fire that ignited in my belly that I couldn’t put out,” she said, “and the only way to quell this was to go out and find out how I could be part of fixing this broken food system.”

Meanwhile, childhood obesity rates were on the rise and diet-related diseases had become the leading cause of death in America. For the first time in more than two centuries, children were not projected to live to be older than their parents. (Some experts say while younger generations may end up living longer, they will do so in poorer health). Stott consulted local nonprofits to see where gaps existed; she decided to focus on healthy eating among children. She started FLC as a pilot at a friend’s after-school program in Oak Park.

The opportunity for the state-of-the-art facility traces back to around 2015 and the development of The Mill at Broadway, an urban infill project of loftstyle housing. The developer had to mitigate the impact of building on open space. Stott says restaurateur Josh Nelson, of Selland Family Restaurants, connected her with the developer, and FLC became part of a burgeoning partnership with SCUSD and City of Sacramento.

“The dream really started to materialize,” Stott says.

FLC held the facility’s official ribbon cutting in September 2022. The entire 2.5 acres and the facility are owned by the school district. The City has two easements, which include a community garden run by its Department of Parks and Recreation (plots are available to rent) and the student farm, which FLC operates.

With the facility’s commercial prep kitchen, FLC staff pack up utensils, equipment and produce to then provide free, hands-on cooking classes during after-school programs at local campuses. “The main thing that Food Literacy Center does is we pack up all these crates and wagons, and we load our cars and we drive away from here,” Stott said.

Food Literacy Center is now in 23 schools in three districts, which include SCUSD, Robla School District and Washington Unified School District, with a goal to be in 40 campuses by 2027. The organization serves grades kindergarten through sixth, but is also in Luther Burbank High School and aims to eventually work with other middle schools and high schools.

“We are growing and expanding,” Stott said. “The need obviously continues to rise, because we’re targeting kids who are at highest risk for diet-related disease, and those kids are the kids who are hungry. So this is a combination food-access solution [and] health prevention, because the kids who don’t have enough to eat tend to only have access to those very high-calorie, low-nutritional type foods.”

H.R. 1, Trump’s “One Big, Beautiful Bill,” signed into law in July 2025, eliminated federal funding for SNAP nutrition education. As a result, in California, the CalFresh Healthy Living nutrition education program will cease operations by this summer, after more than 30 years of programming.

The elimination of federal funds for nutrition education is just one part of the $186 billion cuts to SNAP over the next decade, which experts say could lead to more food insecurity and hunger. SNAP provides families at or below 130% of the poverty line money to buy food with EBT cards. About 42 million people received SNAP benefits in 2023 (the most recent data available), children under 18 accounted for 39% of participants.

In California, an estimated 732,000 residents may lose SNAP benefits due to new eligibility and time limit requirements, which go into effect in April and June, according to the California Association of Food Banks.

The average income for families in Sacramento’s Marina Vista and nearby Alder Grove communities is about $19,500 annually, according to Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency. Of Leataata Floyd’s roughly 220 students, 94% are considered “socioeconomically disadvantaged.” All of the campuses served by Food Literacy Center are Title 1 schools.

FLC has found that food access is greatly needed in today’s economic climate. They used to do occasional food distributions, usually before holiday breaks when kids wouldn’t be able to access school lunches. Now they regularly get calls from principals. One type of distribution they offer is an after-school kids farmers market, using food from food banks; the children get fake money to shop. These are popular events among the families FLC serves.

“They’re just having the hardest time making ends meet, because as the price of everything goes up, their wages are not,” Stott said. “We are seeing that folks just really need free food because they need what little budget they do have for other things.”

In January, Food Literacy Center, which had assumed operations of the Oak Park Farmers Market in 2023, announced in a video the closure of the once-popular market started in 2010 that had run Saturdays from April to November. Stott said the financial reality of the market made it clear they had no choice but to shutter it, and to instead reach more families with their school cooking and nutrition program.

In the video, Stott stated they spent $10,000 per market, but only reached an average of 40 EBT customers each week. That was a cost of $250 per EBT customer, she said, adding that the FLC program is more cost-effective, reaching 800 food-insecure kids per week, for a cost of about $16 per student, per week.

‘Favorite thing ever’

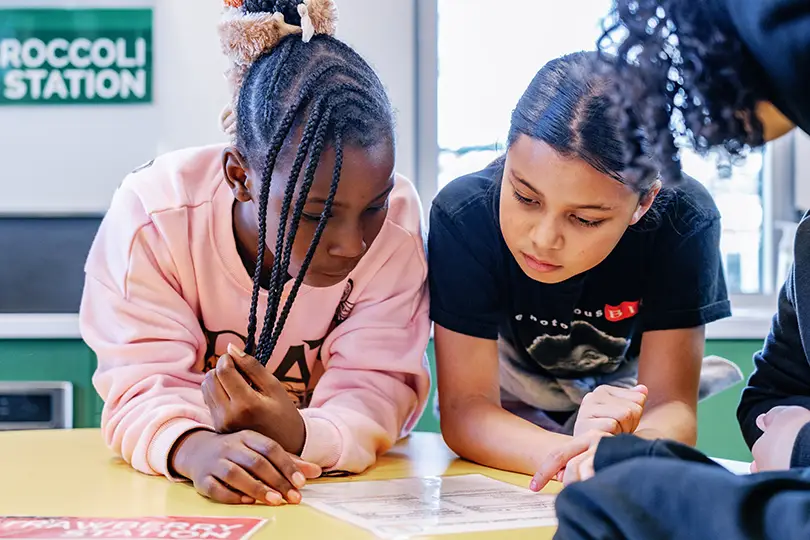

On a February afternoon, 21 students in a fourth-fifth grade class from Leataatta Floyd gathered at Food Literacy Center for a cooking class, which they do weekly for one trimester. They go there during the school day to receive their health and science education.

Their instructor, Sabrina White, proceeded to teach them about their produce of the day — daikon radish — which the children taste-tested, and most then promptly spit into the trash. They learned about how carbohydrates give people energy, and the differences between complex and simple forms.

Fifth-grader Elizabeth, 10, said attending the cooking class has led her to eat more fruits and vegetables. “I really like oranges,” she said. “I eat oranges with every meal.”

After a matching game with carbohydrates and practice reading a food label, it was time for the children’s favorite part of the class: preparing and eating their meal. On this day, they made oatmeal — their first time using the workstations’ stove tops — topped with honey, orange zest, cinnamon and apples they had chopped.

“They love, love cooking class,” said their teacher, Allison Scranton, who is in her first year with the school. “It’s their favorite thing ever. Today, they were melting down and I was like, ‘You’re going to use the stove for the first time, you do not want to miss this.’”

The cooking class gets children to work together to prepare and share a meal, and they are constantly trying new foods. “There was a sunbutter and peaches recipe,” Scranton said. “One kid was nervous to try it. He just took one bite, and he looked at me and was like, ‘Where can I buy this? My mom needs to buy this.’ Which is so cool.”

To wrap up the class, the kids suggested other fruit they could put in oatmeal — strawberries, blueberries, dried bananas.

“I feel like it’s better when you put more fruit in it,” Elizabeth said, as she ate the last bit of her oatmeal. “It really has a good flavor to it and it’s very healthy. I would love to eat this in my everyday life.”

This shift in thinking is the result of partners working together and funders with vision to change the culture around schools and healthy eating. Stott said they are getting closer, even as the need continues to grow.

“When you start in a new school, all the kids are hesitant,” Stott said. “But when you’ve been in a school for three, four or five years, you get kindergarteners who grow up hearing stories about the Food Literacy program … and they’re not even hesitant. They’re just like, ‘My sister does that, she’s in fourth grade, and I can’t wait to do it too.’”

Diana Flores, executive director of SCUSD’s Nutrition Services, Central Kitchen & Distribution Services, agrees that it takes a big mental shift to get children to eat healthy foods if they haven’t been exposed to them before.

Her district has focused on improving school meal programs, which are difficult to execute due to cost limitations, facility challenges, understaffing and lack of sufficient money for food, said Flores. With a background in the restaurant industry, she knew there were ways the district could do better.

“Slowly, but surely, [we] started changing our menus at the high schools because we had more staff there and bigger kitchens and the right facilities, and we had a lot of success,” Flores said. “We could never get there for our elementary students because the kitchens are smaller and there’s not enough staff.”

To meet its goals, SCUSD joined forces with FLC and Soil Born Farms to advocate for the Central Kitchen, a ballot measure-funded facility opened in 2021 where scratch-made school meals are prepared using local sourcing. (Flores said about 65% of the menu currently is made from scratch food, but a more feasible long-term percentage is likely around 50%.)

“We’re super excited about where we’re at,” Flores said. “But a lot of it relies on our students actually changing their taste profiles and not wanting chicken nuggets and cheese pizza and corn dogs all the time, and wanting to eat more dinner-style, healthy options and scratch made.”

The Central Kitchen tries to meet different cultures by producing scratchmade meals like chicken pot pies, chilli, refried beans, tacos and butter chicken. But what the district is not able to do is teach students nutritional education, which is why the partnership with Food Literacy Center is critical, said Flores, who wants food literacy to happen in all grades K-12 for lifelong learning habits.

“When home economics and basic cooking left schools decades ago, I do think that’s a problem,” Flores said. “We have multiple generations of students graduating from school that have never learned to cook. If you don’t know how to cook, you’re not eating healthy at home. … And then we’re seeing, now, poor health outcomes of this next generation … and it’s all related to diet-related diseases.”

Flores believes in what Food Literacy Center does because she has observed the difference the education makes, between children willing to try a healthy vegetable, for instance, and those who are fearful and do not know different types of produce.

“We would have a zucchini and a cucumber in our hands — and we’re like, ‘Hey, can you tell me what these are?’ And they didn’t even know they were different. But if you go to Food Literacy schools, they know that’s [a] cucumber,” Flores said.

Soil Born Farms, along the American River in Rancho Cordova, has worked with FLC since Stott’s early days running the organization. As part of this trifecta partnership, Soil Born runs a school gardens program where children learn how produce is grown and what is in season; SCUSD has the same items in its school salad bars through its Central Kitchen; and FLC teaches the children how to cook and prepare the healthy, seasonal produce for themselves.

“Food Literacy Center has a beautiful facility and culinary programs that they’re aspiring to put in 40 after-school programs,” said Shawn Harrison, co-founder and co-director of Soil Born. “That’s a real game changer. Combined with a network of active school gardens and a Central Kitchen that does scratch cooking and local sourcing, including from our own farm, we are now approaching a real systems change that’s about getting good, healthy food into kids’ bodies every day for some of our most under-resourced students in Sacramento.”

Designed with children in mind

The 1-acre farm behind the Food Literacy Center facility was a vacant lot for so long the weeds took over and farmers have had to fight to reclaim the land.

The crew is doing occultation where weeds are covered with light-blocking tarps that kill off the weeds and eliminate the need for spraying pesticides, also producing healthier soil. The kids work on a small portion of the land, with the staff farm coordinator, Erin Morris, overseeing the whole space.

Morris majored in international agricultural development but didn’t use her degree post-college, instead doing small business development in San Francisco. The pandemic made her rethink her career, and she completed a farmer apprenticeship at the Center for Land-Based Learning in Woodland. In September 2024, she got the job at Food Literacy Center — and had her work cut out for her.

“During the interview, we walked out, we took a tour, and my first assessment was this is like 90% weeds out here,” she said, with a laugh. In particular, the Johnson grass was a difficult weed to kill. “I feel like I’ve been pretty successful. A lot of it’s gone, but OK, it’s a farm — always gonna have a couple of weeds on it.”

In early February, the farm was growing its cool season crops, including garlic, collards, kale, cabbage and cauliflower. Morris’s crop plans for upcoming seasons will be based partly on community feedback from surrounding families. “We’re growing stuff in anticipation of seeing how the community either likes or doesn’t like what we’re growing, and then being able to adjust from there,” she said.

The children may not always like the produce, such as the radishes they grow, but seeing the connection between the field and what they eat makes it exciting. FLC designed the farm with children in mind, for instance with wider pathways than are found on a production farm.

“I designed it with the thought of: There’s nothing out here that a little kid could touch something and completely ruin it,” Morris said. “You know, they’re kids. They’re gonna run around. They’re gonna step on plants on accident. It’s part of the fun of being outside and being able to experience that.”

Once the cooking trimester is done this spring, the students will begin their farming trimester. When they visit the farm with the strawberry tree, they will find a path that travels right down the middle. That was intentional, appealing to a child’s natural instinct to see a long straightaway – and sprint from one end to the other.

“Every time we bring a class here, we let them run,” Stott said. “You can’t keep them from it, at least not very successfully. We build it into our program that they can run down and back, and every single kid wants to do it. … It’s awesome to watch.”

This story is part of a six-part series called “Solving California,” a project of the Solving Sacramento journalism collaborative that explores models to improve California. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, CapRadio, Capitol Weekly, Hmong Daily News, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review and Sacramento Observer. Support stories like these here, and sign up for our monthly newsletter.

By Sena Christian